“When I was a child in rural England, starlings would flock in the thousands on telephone wires. It presaged the beginning of winter, and it invoked a certain sense of melancholy. I would like to think the paintings do the same — a certain sense of beauty, yet sadness at the same time,” [i] says the artist Richard Butler.

Songs for starlings — the title Butler has given this exhibition — like the metaphorical language of birds, speaks truths about our lives. And just as with the songs of birds, an exact reading of Butler paintings is impossible. Meaning is only insinuated by a few visual clues. In some ways, Butler’s paintings become allegorical stories full of paradoxes and riddles. And the riddle starts with the artist himself.

Richard Butler is an artist whose work ranges from painting to music. Born in London, England in 1956, his first love was painting. He studied at a leading art college in the United Kingdom, the Epsom School of Art and Design (now Surrey Institute of Art & Design, University College) just southwest of central London. Shortly after graduating in 1977, he became a founder, the lead singer and songwriter of the British post-punk/new wave band The Psychedelic Furs. Quickly gaining critical and commercial success, Butler’s musical career invariably eclipsed his life as a painter for almost two decades (touring internationally and releasing nine studio albums and two live albums over 40 years). In the 1990s, while touring worldwide, Butler returned to his first love of painting, and has steadily built a body of work, which is both intimate and universal in its appeal.

Although reticent to discuss it, Butler’s music and paintings are inextricably linked.

Butler’s music is known as artistic, dark and atmospheric, with introspective lyrics.

“I never really think of my painting and music being connected. If pressed, I would say that both share a certain melancholy.” [ii]

Butler’s paintings are expressions of his inner world, a reflection of his own personal journey, and born from his thoughts on love, loss, identity, doubt, alienation, and the human condition.

“Love my way, it’s a new road I follow where my mind goes,

So swallow all your tears my love

And put on your new face…” [iii]

Part introspection, part confession, part invention, part dream: Butler’s paintings are unabashedly emotional. He is engaged in the vicissitudes of the constructed image, that is, the image’s change and evolution, the metamorphosis from one context to another – from youth and innocence to the constrictions of life’s lessons and the consequences of those changes.

‘The Hollow Men’ (1925) [iv] is a poem by T.S. Eliot that explores themes of religious confusion, despair, and the state of the world in disarray. But unlike the spiritual decay of Eliot’s hollow men “stuffed with straw” and empty of substance, Butler’s subjects resist the abyss of absolute nothingness, and instead, reach for a feeling of wistful melancholia and mystery.

Every Richard Butler painting is a portrait. Butler explains, “…a portrait has a focus and a presence, and as much as I might like to look at a picture of flowers by Chardin, it does not have the immediacy of a Rembrandt or a Holbein. The skin tones, the fact that it is a person—I want to try to do that.” [v]

Making his unhurried way along the most heavily trodden path of painting — that of portraiture — Butler’s portraits are dark, somber, mysterious and connected somehow to our collective anxieties. Butler prompts the viewer to experience them, to be conscious of following the rules, implicit and explicit, that lend coherence to images, literary and historic references, and tradition.

The great Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) said, “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter; it is rather the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself.” [vi]

“My images surprise me,” says Butler. “Although, there is always a ‘recognition’ —recognition of myself I suppose. In a way I think all of my paintings are self-portraits in that though the face I am painting may not be my own, the feeling I get back from the painting is certainly an important element of my own psyche. Hence the ‘recognition.’” [vii] The psyche of the artist — the mind, the soul, and the spirit — is revealed through the semiotics of images as meaning.

Richard Butler’s paintings are his songs for starlings. And we are the starlings.

“Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.” [viii]

— T.S. Eliot

Since antiquity, migrating birds have been seen as souls and symbols of freedom.

According to the Koran, the “language of birds” is spiritual knowledge, and is related to the soul. In Abrahamic and European traditions, the language of birds is postulated as a

mystical, perfect and divine language. Migrating birds – such as those of 12th-century Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar [ix] in his fable The Conference of the Birds, and those of 10th-century Islamic philosopher and physician Avicenna’s (980-1036) allegorical Recital of the Bird [x] – are souls searching for redemption. As symbols of freedom, intelligence, courage, and transcendence, birds have historically connected the past with the present and the future. Moving in flocks of thousands, searching for a place to land, migrating the continents, huge flocks of starlings speak many languages, mimicking words and noises and the songs of other birds.

[i] Richard Butler, email message to author, October 23, 2023.

[ii] Richard Butler, “Richard Butler on Art, Music and Melancholy,” interview by Sandra Hale Schulman, Medium, June 3, 2020, https://sandraschulman.medium.com/ richard-butler-on-art-music-and-melancholy-9d2bcf23484f

[iii] Richard Butler, “Love My Way,” track 1 on The Psychedelic Furs third studio album Forever Now, 1982, Columbia/CBS.

[iv] T.S. Eliot, “The Hollow Men,” in The Complete Poems and Plays 1909-1950 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1971), stanza 1, p. 56.

[v] Richard Butler, “Richard Butler,” interview by Lyle Rexer, BOMB magazine, August 29, 2013, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/richard-butler/

[vi] Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Grey (New York: Tribeca Books, 2010), p. 23.

[viii] T.S. Eliot (1888-1965), from Burnt Norton, poem one of Four Quartets, 1935, http://www.davidgorman.com/4quartets/1-norton.html

[ix] Farid Ud-Din Attar, The Conference of The Birds. The Clear Light Series (Boulder: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1971), p. 135.

[x] Avicenna (Ibn Sina), “The Recital of the Bird,” in Henry Corbin, Avicenna and the Visionary Recital: (Mythos Series), ix-xiv. (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960), pp. 168-203.

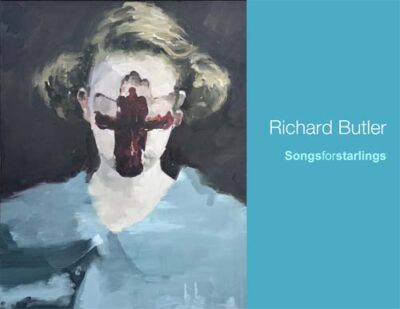

“The close up portraiture becomes profoundly macabre in the eerie work of Richard Butler, both legendary rock star and painter. As the founder, lead singer and songwriter of the English post-punk rock band The Psychedelic Furs, Butler studied painting at The Epsom School of Art & Design (now the Surrey Institute for Art and Design). Butler’s portraits are haunting tableaux, blurring any distinction between portraiture and contemporary art as they spin in intoxicated slow motion.

In the small portrait “Ashwednesday,” Butler depicts his daughter — “Some ninety percent of the paintings I make are based upon images of my daughter, usually distorted in one way or another,” he explains. “She has become a cipher for me, an every man/woman.” Butler creates dark portraits with abstract elements covering parts of his subjects’ faces or hovering in midair. With titles like “confessionalsinner,” “devilsbreath,” “whenisaidiloveyouilied,” and “yourheroestoowillbeforgotten,” Butler’s canvases combine the melancholy with a surreal, dream-like state bathed in a kind of eerie silence.

Often, Butler’s subject’s face will be obscured by thick make-up, masks, confessional screens, veils and shrouds, creating a labyrinth of psychological layers which the viewer is invited to transverse, and gain an understanding of the subject as well as the self. Butler combines classic beauty and the surreal, even the grotesque, in haunting works that the artist insists “are just paintings.” Many are relatively small, almost life-sized, putting the viewer face to face with his subjects. Butler has said he thinks of these portraits as self-portraits — that they reflect feelings from his “own psyche.”

Wendy M. Blazier,

Miami, 2019

Click here to view available works